The "F1" Playbook

How Apple Studios created a successful blockbuster sports film at a perilous moment for their theatrical strategy.

By many metrics, F1 is already the most successful original sports film of all time. I suppose that depends on your definitions of the term “sports movie” (whoever included the Fast and Furious franchise on the “List of highest-grossing sports films” Wikipedia entry should be ashamed of themselves), but the point is that F1—a non-sequel, non-spinoff, non-franchise film whose marketing campaign rests upon the powers of the Formula One brand and Brad Pitt’s coiffed hair—has grossed over $500 million worldwide: a mighty sum for an original film about fast cars.

That’s a win for Apple Studios, whose previous theatrical endeavors have failed to turn anything resembling a profit (possible exception given to 2023’s Napoleon) . The quality of those films range from good (Killers of the Flower Moon) to bad (Argylle) to forgettable (Fly Me to the Moon), and while I’m inclined to praise Apple for taking risks on original movies on real movie screens, it’s also hard to ignore that it was burning up to $1 billion a year in its attempts to do so. Apple eventually took notice: In August of 2024, during the lead-up to the theatrical release of the George Clooney- and Brad Pitt-starrer Wolfs, tracking numbers dipped so low that they not only pulled the plug on the film’s theatrical release, but also on the rest of their theatrical endeavors. Apple films would now show for only the shortest of theatrical release windows before being shunted off to Apple TV+.

With its massive budget and event-film marketing strategy, F1 appears to be the last vestige of Apple’s discarded theatrical strategy. It is with some irony, then, that F1 has transformed itself into Apple’s biggest hit, and while it’s hard to proclaim with any certainty whether they should pivot back to their previous theatrical approach (much as I personally believe we would all benefit if the world’s biggest company used its $3 trillion valuation towards cinematic ends), it’s at least worth looking at the key reasons for F1’s success. Let’s get down to it.

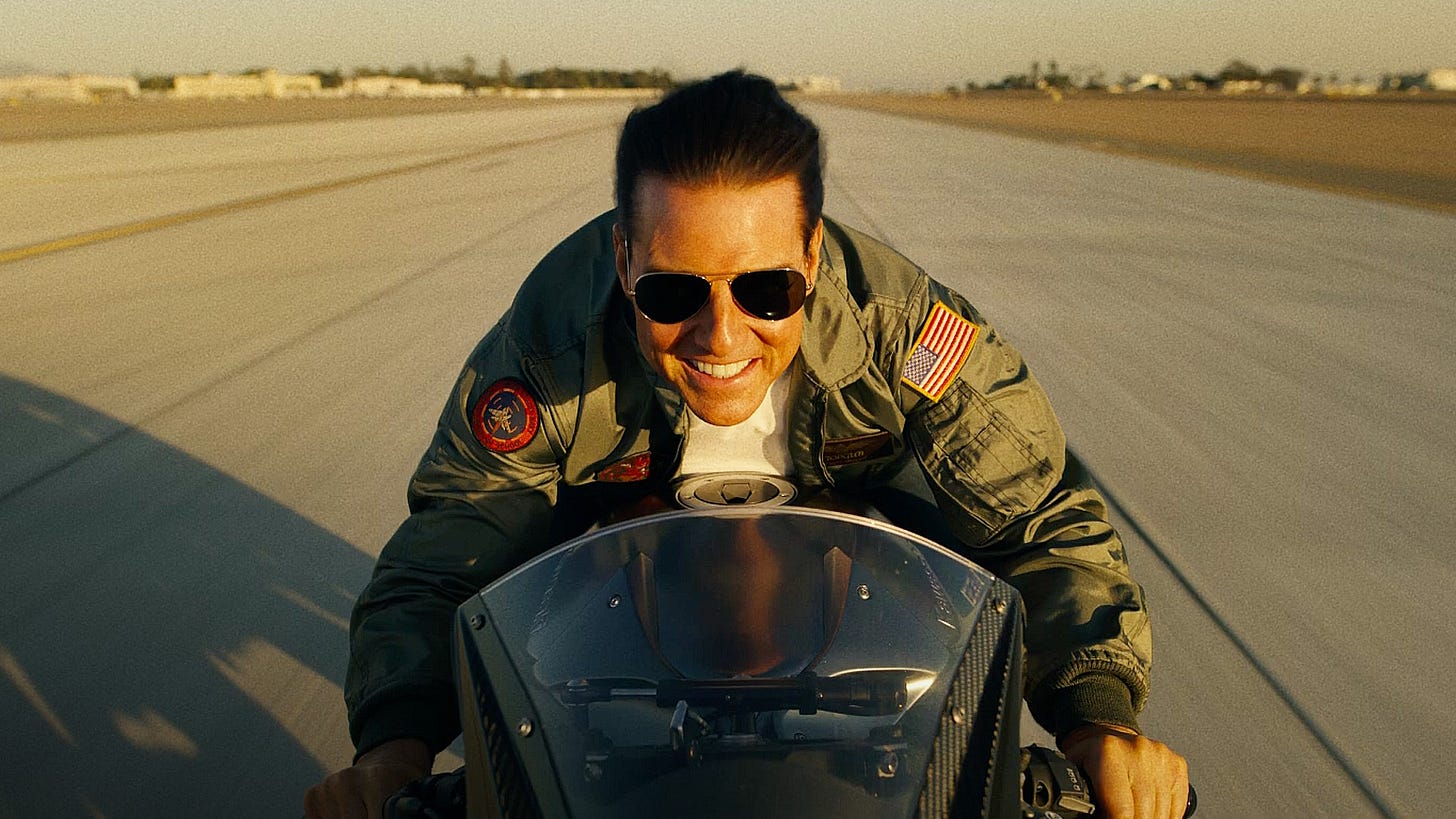

The Top Gun: Maverick Playbook

Top Gun: Maverick was the movie America needed in its post-COVID heyday: a legacyquel that played passionately on our nostalgia for American jingoism and the music of Kenny Loggins. It was a blockbuster that blended stardom, spectacle, and IP commercialism without ever feeling distasteful, and resultingly broke all kinds of domestic box office records, becoming the fifth highest-grossing movie in domestic box office history and the biggest of Tom Cruise’s career.

As such, it’s not entirely surprising that F1—Apple’s largest film investment to date— pulls 90% of its story beats from the Maverick playbook. All the original Maverick behind-the-scenes crew (writer Ehren Kruger, director Joseph Kosinski, and megaproducer Jerry Bruckheimer) reprise their same roles for F1, and they bring with them a near-identical story. As in Maverick, F1 tells the story of a weathered sexagenarian returning to the world of big mechanical vehicles that go zoom, except that Pete “Maverick” Mitchell is here replaced with Sonny Hayes (Brad Pitt), a one-time Formula One golden child whose life has since gone downhill. Like Maverick, Sonny is offered a chance at redemption when his old teammate (played by Javier Bardem) offers him a chance to drive for APXGP, a new-on-the-block F1 company.

There’s a degree of 1980s schlock to this plotline that comes that comes dangerously close to kitsch, particularly in how the films asks us to believe that the 61-year-old Pitt could genuinely compete with young upstart Joshua Pearce (Damson Idris). This is another plotline taken almost verbatim from Maverick, in which old man Tom Cruise spars with thirtysomething Miles Teller for top flying duties. But here as there, we believe it anyway, not least because Kruger, Kosinski, and Bruckheimer shoot this well-trodden sports narrative with an awe-inspiring precision.

Kosinski, who worked as an architectural engineer prior to being a filmmaker, iterated upon the camera system he previously designed for Maverick to be able to attach to F1 cars hitting 140mph, leading to some genuinely tremendous racing sequences captured not just from the top down, but inside the car itself. There’s a magnificent sense of high-octane immersion when the camera, positioned on the hood of the car, whip-pans from Brad Pitt’s face to the 200mph vehicle alongside him. It’s these kinds of showy, technically-minded camera moves that cement Kosinski as a brilliant engineer-auteur—the perfect blockbuster mind for a high-concept Maverick retread.

The Elder Movie Star Playbook

Maverick was a smash hit for all the reasons stated above, but blockbuster status was not all the film had on its mind: it was also a self-mythologizing metaphor for the career of its leading man. The story of Pete Mitchell—obsessive fighter pilot who spends his elder years test-flying hypersonic jets to Mach 10—served as the ideal vehicle for Tom Cruise: the psychopath whose commitment to action filmmaking would revitalize cinema if it was the last thing he did. And just as Maverick wove the hard-bitten insanity of latter-day Tom Cruise into the structure of its narrative, so too does F1 capture the powers and paradoxes of Brad Pitt in his fourth decade of stardom.

In the post-Brangelina phase of his career—one dogged by allegations of abuse and alcoholism—Pitt’s roles have shifted away from the outright debonair of his characters in Fight Club, Ocean’s Eleven, and Mr. and Mrs. Smith, and towards something slightly more sinister. In this new era, there is a newfound layer of misogyny and violence undercutting what was once Pitt’s effortless cool. In Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, he is the handsome stuntman—who may have also murdered his wife. In Babylon, he is elder movie star loved by all—who is also an alcoholic, fame-obsessed, and past his prime.

F1 understands these late-career principles and utilizes them to self-mythologizing ends. Even though Sonny Hayes is the embodiment of silver-fox suave (and Pitt is more than happy to play him as the elder hunk who strides confidently down racetracks, top buttons undone as though he’s just walked off the set of a perfume commercial), his dashing appearance is nevertheless marred by his public failures. Early on, we learn that Sonny has become a thrice-divorced gambling addict since his salad days at Formula One, and it’s impossible not to think of how the public perception around Pitt has become similarly tarnished.

F1 is not a critical interrogation of stardom, however, but an act of deification. Sonny Hayes is the vehicle through which Pitt reclaims the hero mantle: Sonny becomes an old-school mentor to his young teammate Joshua; he inspires the APXGP team to collective victory; he woos Irish babe Kate McKenna (Kerry Condon), who also happens to be the team’s technical director. Ironically, this is not Pitt at his best: His mumbly line delivery and laissez-faire demeanor gives the sense that he is checked out, when we should believe that this ronin of a racecar driver is utterly locked in. It’s a testament to Pitt’s continuing stardom that F1—a film otherwise limited by its sports movie confines—becomes the thrill ride that it ultimately is.

The Barbie playbook

Did you know that Formula One has close to a billion fans worldwide? I certainly didn’t, and it goes some way in explaining how an “original” film like F1 could manage to become such a worldwide smash. Because it’s not an original film. Rather, it is the byproduct of a gargantuan global sports machine that functions identically to IP. (How else could this non-spinoff, non-sequel, non-franchise film could make over $500 million worldwide?)

In this way, the film that F1 most resembles is not Top Gun: Maverick, but Barbie—Greta Gerwig’s megahit 2023 comedy that made over $1.4 billion worldwide. Yes, some of that revenue can be traced to the film being an excellent piece of entertainment, but the bulk of its box office stems from the audience’s preestablished knowledge of the Barbie doll itself. Audiences didn’t care about a new comedy from Greta Gerwig; they cared about seeing Margot Robbie play a Barbie doll on the big screen.

Formula One is not quite the omnipresent force that is Barbie, but the principle is the same. With something close to a billion fans worldwide, a good chunk of the folks walking in the door aren’t walking in for Brad Pitt, but for the Formula One brand. I wrote about this trend in my last post, particularly with regard to A Minecraft Movie and the trend of first-time IP Hollywood filmmaking. Established brands—be they toys, sports franchises, or videogames—are increasingly becoming the basis for Hollywood films, with F1 and Barbie both being high-end examples in this mold. They are films that translate the emotional essence of a well-known public asset into genre-appropriate cinema—and they are an increasingly important factor in getting butts in seats.

The Streaming Service Playbook

In the age of the streaming service, what constitutes a hit film? As the lines between production, distribution, and exhibition become increasingly blurrier, that question is harder to answer than ever. What do we call a movie that flops in theaters but puts up massive numbers on streaming? Can a movie with a budget of $200 million be considered a hit if it never released in theaters? With the budgets that they have, do tech companies like Apple and Amazon even care?

Earlier in this post, I called F1 “a win for Apple Studios”. I stand by that sentence, but it’s worth noting that that isn’t quite true in the traditional sense of profitability. F1’s massive budget (different sources report anywhere from $200 to $300 million) indicates that it would need to make anywhere from $500 to $750 million just to break even. To date, the film has done pretty well, grossing around $530 million globally. And while that might be enough to crack the top ten highest-grossing movies of the year so far, it likely isn’t enough to balance a studio’s checkbook.

But for Apple, a company whose financial investments in the movie business constitute a fraction of its overall valuation, the notion of a “hit film” isn’t just in the numbers. Apple Studio exists in large part to give its parent company a sense of cultural prestige, and under those terms, F1 is an unequivocal success. It is endlessly pleasing to the egos of Tim Cook (Apple CEO) and Eddy Cue (head of Apple TV+) that F1 is in the cultural conversation. However financially lacking that $530 million global revenue may ultimately be, it nevertheless serves as an indicator that Apple can be a genuine player in the movie busines (and at a time of perceived desperation, no less).

The Event Movie Playbook

Put all these elements in place—a high-concept 80s narrative, a redemption arc for an aging movie star, a well-known sports brand, and a streaming service who can juke the stats—and you might just have a hit on your hands. But a hit requires a good marketing team, and it is here that F1 gets its engine purring.

F1 is the definition of an Event Movie: a blockbuster movie that must be experienced in theaters, rather than at home. This was true from the moment Apple released its masterful 60-second Super Bowl spot—a sensorial montage of speed, romance, and competition, and one of the best trailers of the 2020s. This throwback blockbuster, we were told, would scratch an itch not satisfied by the typical deluge of sequels and live-action remakes. This was the movie you had to see in theaters.

It helps that the film could back up its marketing claims. Kosinski’s camerawork is astounding, providing the sense that it was engineered within an inch of its life, and more than earning the price of an IMAX ticket. The same goes for Brad Pitt: movie stardom is rarely so well-utilized as well as it is here, and at a time when it is sorely needed. Should Apple choose to remain in the theatrical business, they would do well to replicate strategy or two from the F1 playbook.