"The Marvels" and the Critic-Proof Marvel Machine

The Marvel Cinematic Universe has become Too Big To Fail.

“These movies are designed to be critic-proof.”

So said A.O. Scott, longtime film critic for The New York Times, about the Marvel Cinematic Universe in his exit interview from the position earlier this year. This is the media juggernaut that has dominated blockbuster cinema for the past decade and a half, and Scott knows it. “You create something so enormous and so powerful,” he argued, that it “seems like just a fact of nature almost—it just sort of crushes any dissenting voice or point of view and doesn’t give you a lot to talk about.”

This quote kept ringing through my head as I sat watching The Marvels, the 33rd entry in the ever-bloated MCU, in a Thursday preview screening filled with nothing but superfans. The movie is not bad per se—it is eminently forgettable, the kind of big-budget entertainment that won’t stick in your mind even ten minutes after leaving the theater. It is neither good nor bad; you will watch it and forget it; you will consume this CGI nonsense and go on with your life.

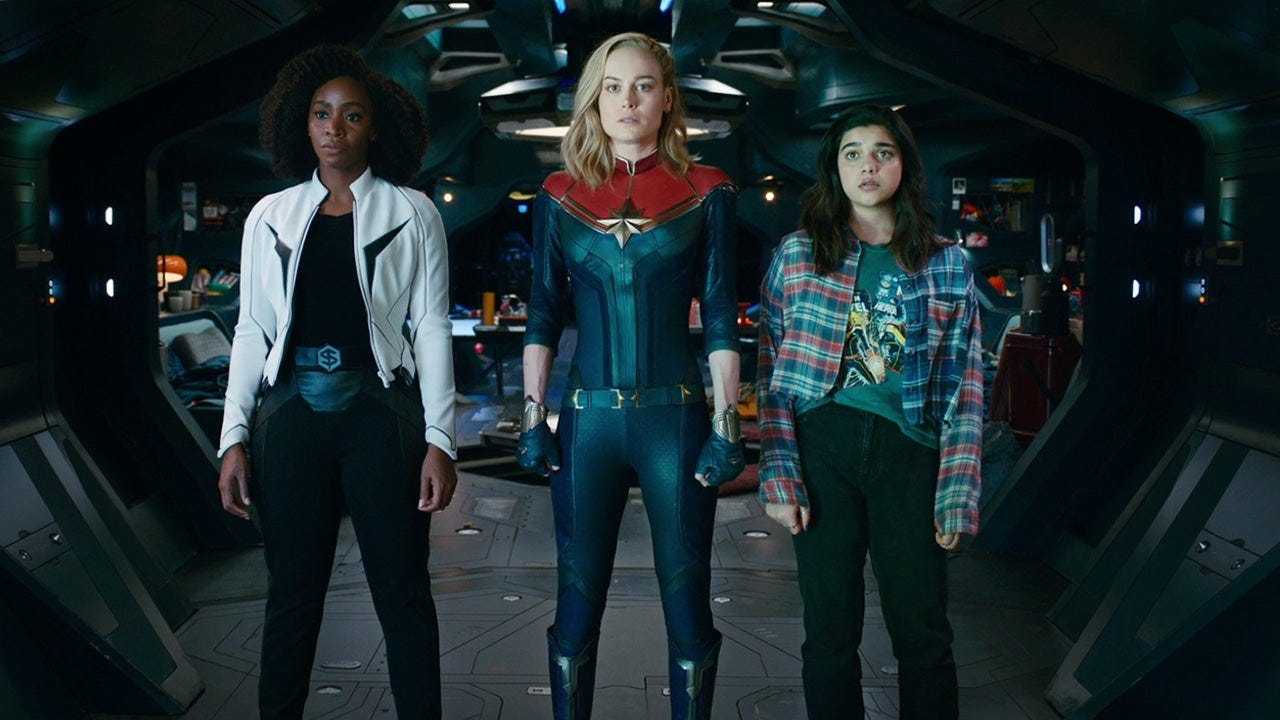

The film is a superhero team-up movie between three disconnected corners of the MCU: Carol Danvers (Brie Larson) from Captain Marvel, Monica Rambeau (Teyonah Parris) from WandaVision, and Kamala Khan (Iman Vellani) from Ms. Marvel. The three actors are talented enough to create entertaining girl-group chemistry, one would think, but it never quite comes together as it should, perhaps because two of the three characters could hardly be called “characters” in the first place. Larson, an excellent actor, was miscast as Danvers in 2019’s Captain Marvel, where she became the MCU’s ill-fated version of Superman—an invincible and emotionally inaccessible alien who can fly and shoot blobs of CGI energy out of her fists. Parris does a fine job as Rambeau, a scientist who can control different forms of energy, but her character doesn’t extend much beyond those superpowered traits. She has a familial relationship with Danvers (she was a child during the events of Captain Marvel) that never gets explored to any substance in the film’s 100-minute runtime. Meanwhile, about 90% of the film’s charm hinges on Vellani, who plays Kamala Khan as an effortlessly endearing Captain Marvel superfan. Her overriding obsession with Carol Danvers elicits the film’s spare moments of authentic laughter.

The script (by Nia DaCosta, Megan McDonnell and Elissa Karasik) packs at least the embryo of an interesting idea. In the previous Captain Marvel film, Danvers nearly destroyed the planet of Hala, home to the alien species the Kree. Villains in the previous film, the Kree are now left in a desolate position, resorting to terrorist-adjacent uprising tactics in order to cleanse Hala from total environmental collapse. There’s a kernel of sophistication in the idea of Captain Marvel as metaphor for broken American interventionism, particularly as it pertains to the Middle East in the wake of 9/11. (This is something that Zack Snyder also tried to do with the character of Superman in Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice. Too bad that’s one of the worst films ever made.) But director Nia DaCosta fails to engage with these ideas with any intention whatsoever: The Marvels prefers instead to lean into the awkward aesthetic of a fun girls’ night with a destructive tribal conflict occurring in the background.

So the film doesn’t quite engage with the compelling ideas of its screenplay, but does it at least get to have some superpowered fun? On occasion, yes! The Marvels is at its best when at its most ridiculous, which creeps into the film regularly enough to keep us entertained. There’s an early fight sequence in which the three superpowered heroines swap places with each other whenever they use their powers, leading to some hijinks in which Danvers and Rambeau crash in on the home of Kamala’s sitcom-ready household in Jersey City. (Kamala’s Pakistani-American parents are played sweetly by Zenobia Shroff and Mohan Kapur; her older brother is played by Saagar Shaikh, also a welcome presence.) There’s a song-and-dance number involving K-drama star Park Seo-joon that is thoroughly bad, but has a kind of famous actors getting drunk in Crete sort of energy that invokes the charm of something like Mamma Mia! There’s also a madcap setpiece an exploding starship, tentacle-mouthed cats, and a music cue from the Andrew Lloyd Webber stage musical, Cats. (Not to be confused with the 2019 horror film, Cats.) DaCosta has a tremendous amount of fun with these sequences, and it’s refreshing that a Marvel film has the chance to engage in pure camp.

All that fun gets bogged down by the usual insipid Marvel tropes, the kind that any audience member should by this point understand. The film’s villain, Dar-Benn (Zawe Ashton), is a typically half-baked plot device without proper development or screen time. The aforementioned relationship between Danvers and Rambeau—their whole surrogate aunt-niece thing—never coheres into anything resembling authentic human emotion. The film also has the typical Marvel overreliance on computer-generated effects, especially in a concluding sequence with CGI humans throwing CGI globs at CGI aliens and vice versa. We’ve come to expect this kind of mind-numbing computerization from Marvel, but becoming numb to the machine doesn’t change the fact that watching energy blasts smash into each other for twenty minutes is about as engaging as a 3:00 AM binge-watch of competitive bowling.

The Marvel Machine

“Mind-numbing” is the operative word here, because at the end of the day, the artistic quality of The Marvels doesn’t matter. The film being good or bad will not affect whether fans will cheer at the Marvel logo, nor will it affect their freakouts when a long-anticipated character is introduced in a post-credits sequence. When I tell you not only that audiences not only applauded at the Marvel logo and the post-credits sequence, but also at the AMC logo—when Nicole Kidman did her whole “We come to this place” onscreen advertisement—know that I am telling the truth, and know I have never seen more dystopian corporatism inside an American multiplex. These applauses will keep the fans engaged, it seems, while the rest of the world fails to notice that the 33rd film in the Marvel Cinematic Universe has come and gone, forgotten to the eventual wilds of a Disney+ digital silo.

As the Marvel Cinematic Universe has evolved from an innovative series of interconnected movies to the overblown entertainment machine that it is today, it becomes increasingly difficult to take in these films with any purposeful criticism. It’s hard to put thought into something as thoughtless as Thor: Love and Thunder, to give substance to something as vacuous as Eternals, to find artistry in anything as creatively impotent as Ant-Man and the Wasp: Quantumania. There is, at this point, hardly anything to these films beyond their future propagation. Narratives are rendered without emotion or coherent purpose; characters are introduced and then re-introduced on the basis of empty nostalgia; we continue hope-watching on the promise of greatness that never arrives. Slowly, our mental faculties turn to mush as we eagerly anticipate the implementation of the Fantastic Four and the X-Men into an ever-expanding cinematic universe with increasingly little to say.

The last time I tried to write about a Marvel movie was Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 3, and there was hardly any point. I tried to engage with the film’s ideas in the context of Marvel’s churning production cycle, and concluded that the film was quite poor (I am still the only person in the world who thinks this, apparently), but in a way that was uniquely auteurist for the Marvel canon. This is still one my lesser-read entries of the year—understandably so. Neither Marvel fans nor casual moviegoers are going to care about what any one critic is going to have to say about the 32nd entry in the Marvel canon, because both Marvel fans and casual moviegoers know exactly what to expect from so many years of superhero content: they know what they’re walking into. If audiences aren’t going to care what a critic like Richard Brody thinks about Guardians Vol. 3, then they certainly aren’t going to care about the opinion of some half-employed 24-year-old blogging his idiot heart out. (Thanks so much for reading, by the way. Please subscribe.)

One of the funnier things about the current state of film criticism is that the best movies to write about are often those that the fewest people are going to see. My entries on blockbusters—on the aforementioned Guardians Vol. 3, or on the John Wick franchise, for instance—struggled to generate readership, whereas the opposite was true for arthouse films like El Conde or Saint Omer. That’s a bit paradoxical, given that a guaranteed fewer people are going to watch a black-and-white Chilean satire about an autocratic vampire than the spacefaring shoot-em-up of the Guardians franchise. Reading about those movies, on the other hand, is an altogether different question. If my meager readership data is anything to go by (which it surely isn’t, but here we go anyway), then I’d suggest that people who read criticism are less interested in whatever the most recent Big Release is than they are in movies with ideas.

Readership isn’t everything, however, and I can’t deny that I find it hard to turn my attention away from the MCU. The lizard brain that keeps me plugged into the latest box-office data from the most recent legacyquel or Fast and Furious movie is the same brain that keeps me watching nearly everything Marvel has ever produced. Here is an industrial entertainment machine that has tried and occasionally succeeded at creating a movie monoculture for more than half of my twentysomething life. The MCU stays relevant, even as it has curdled into the fatigued and overworked monstrosity that it is today. It bullies its way into our multiplexes, floods our content streams with forgettability, plays endlessly upon our nostalgia for a Robert Downey past. It isn’t going anywhere.

The Balance of Art and Industry

One of the things that makes cinema such an exciting artform to write about is that it is an industry, but the converse is also true: cinema is an exciting industry to write about because it is also an artform. And Marvel, industrial machine that it is, has seen itself more as a corporation than an artform to an extent perhaps greater than any entity in cinema history.

As an industry, then, the MCU seems to have just reached its nadir. The Marvels just had the worst domestic opening weekend for any Marvel movie on record of about $47 million, far too little revenue for a movie which cost a reported $270+ million to make, which doesn’t include an advertising budget that puts the film’s total budget into the ballpark of $350-$400 million. The reasons for this failure are beyond obvious. To fully enjoy The Marvels as intended, you must be able to walk into the theater having seen at least two Disney+ shows in their entirety—WandaVision and Ms. Marvel—which doesn’t account for needing a general familiarity with the MCU’s 33-movie filmography—you’ll need to see somewhere between 20-25 movies, I’d say. All of that combines to a truly staggering amount of screen time just be able to watch a single forgettable 100-minute movie.

All that homework—and it really does feel like homework—doesn’t account for Marvel’s failure to recognize that a crossover movie between Captain Marvel, Ms. Marvel, and Monica Rambeau is simply not what the marketplace is interested in. Brie Larson has already expressed disillusionment with the entire Marvel project after having faced a torrent of toxic backlash from the first film. Monica Rambeau was herself little more than a side character in WandaVision, a show that had almost nothing to do with the world of Captain Marvel. And Ms. Marvel, by all accounts a thoroughly entertaining show, is still the least-watched Marvel series on Disney+.

It isn’t pleasant to reduce a movie down to its industry components like this. Criticism requires engagement with both art and with industry, yes, but criticism is a far better practice when there are actually some artistic qualities to engage with. It’s not that The Marvels has no artistry to it, but when the production and reception processess of a film so overwhelmingly corrupts its artistry, critical engagement begins to feel pointless.

I say all this as someone who has enjoyed a good deal of the movies produced under the MCU banner. As recently as four years ago, Marvel was at the forefront of crackling critical conversations about the nature of cinematic serialization and whether or not an Avengers movie deserved to be invoked alongside the word “cinema.” (Even Martin Scorsese got in on the conversation, remember that?) There were pros and there were cons to the series, but beneath all the premonitions of the death of auteurist filmmaking and the rise of blockbuster roller coaster rides, there was a palpable sense of excitement: excitement that the MCU kept putting out a slate of entertaining blockbusters, excitement that Avengers: Endgame could procure whoops and cheers from an audience during moment that deserved it, excitement at the seismic cultural shift engendered by a singular vision such as Black Panther. There was, in short, a sense that the MCU was opening up the possibilities for what cinema could be.

That excitement is gone. The Marvels is probably the most critic-proof movie in Marvel history, not because it is extraordinarily good or abominably bad, but because it is unbearably forgettable. There is hardly any use talking about The Marvels as entertainment when the film is so overridingly fan-pandering—it overwhelms creativity to the point of no return. Cinema is both an artform and an industry, and it is fair to expect an entity like Marvel to tip in the favor of industry. But a healthy moviegoing environment has the presence of both, and right now, Marvel is nothing but churn.