For the past year I have worked as a contract worker for film festivals in cities along the West Coast. The work itself has varied significantly, but in my still limited experience as a Festival Nomad, one thing remains consistent: a planning period defined by a steady buildup of ever-increasing stress that crescendos into a ten-day rush of adrenaline and far too much caffeine. It’s thrilling work, particularly for extroverts like myself who enjoy nonstop chaos and collective trauma bonding.

The downside to this is that my amount of actual movies I watch at festivals has decreased significantly since beginning this work. So when I touched down in Salt Lake City last Friday as a mere visitor, prepared to sit in theaters and meet fellow festivalgoers, I couldn’t help but feel a bit of whiplash. There was no need to attend to guests or festival operations; I had no plan beyond a movie screening scheduled for 9:00 PM that night. I might have the chance to visit some old friends and colleagues. If I wanted, I could just, like, sit down and watch movies. Is this why people go to film festivals?

The answer to that question is “Yes,” of course, and—despite my feeling of self-conscious disentanglement at this unfamiliar situation—watch movies I did. Over the course of my three-day stay in Park City, I managed to squeeze in five feature films and a block of six short films, which was certainly not bad for a first visit, though it was not as many as I would have liked. My two-screenings-per-day average paled in comparison to critics tearing through four to five movies per day. I was jealous, but then again, that’s their job. This Airplane Mode bullshit is (tragically) just for fun.

Movies weren’t the only reason I was going to Sundance, however. As with all film festivals, Sundance is also a ten-day megaparty. If I wasn’t at one the eight screening venues spread across Park City, I was schmoozing and networking, drinking in bars and partying in nightclubs (the likes of which I shouldn’t have had access to, except that I happened to know the right people). I met up with old colleagues and new acquaintances, each of us excited to be part of this pseudo-exclusive mountain town event. This air of privacy is the thing that makes festivals tick—the private parties, the black-market trading for sold-out movie screenings, the high-profile celebrities surreptitiously wandering the jam-packed festival streets. And, to my great delight, this atmosphere is fully maximized at Sundance. You’ll pass by Will Ferrell, struggling to move past a group of fans clamoring to get a signature; you’ll see Lionel Richie walk onstage to speak with effortless charm about his new documentary. My personal highlight came in the form of a shades-wearing Jay Ellis (of Insecure and Top Gun: Maverick fame), who brushed past me at a bus stop. We made eye contact. I was giddy.

As for the movies, each of the films I saw were world premieres, although admittedly, that sounds more significant than it is. For those who don’t know, much of the excitement behind a film screening at Sundance comes from the possiblity of getting picked up by a distributor. A Sony or a Netflix executive could be sitting in the audience for your film, and if it ends up being to their liking, they might offer you a distribution deal.

This is the point of film festivals in spirit, at least: certain films making their world premiere were well on their way to distribution before they made their first screening. For instance, a movie like The Greatest Night in Pop—a charming and surprisingly heartwarming documentary about the recording of the 1985 megahit charity single We Are the World—was slated for a January Netflix release well before I attended its world premiere; the same is true of the satirical The American Society of Magical Negroes, scheduled to be released in March by Focus Features. Yet their presence at Park City matters nonetheless: These movies are going into wide release anyway, but if they manage to achieve the coveted title of “Sundance hit”—well, it certainly doesn’t hurt their awards chances.

Not that either of those films fall anywhere close to awards contention. They are evidently constructed with too much broad appeal in mind; they are driven by a good-natured optimism that should do well with wider audience, though not with 2025 Oscars voters. Ponyboi, on the other hand—a Safdie brothers-esque crime thriller about an intersex sex worker caught up in the Italian American underworld of New Jersey (or at least a hilariously stereotypical version in which every gangster is named something like “Lucky” or “Two-Tone”)—is aiming for High Artistic Achievements. The film is written and starring intersex filmmaker River Gallo, and is tailor-made for the midnight festival circuit. It features a depiction of poverty and sex work that is grimy to the point of absurdity, with unruly attempts at “gritty realism” (whatever that phrase means anymore) that never quite land with the intensity it aims for. The film’s contrived narrative and over-the-top dream sequences end up placing the tone far closer to The Rocky Horror Picture Show than to The Wire, resulting in a film that is certainly not for me. (Some punchy direction and solid performances are at odds with a script whose clichéd themes it delivers with the subtlety of a sledgehammer.) But at a 10:00 PM screening with an audience cheering at even the most minor narrative turn, it was hard to be upset. The film premiered to the audience at which it belonged.

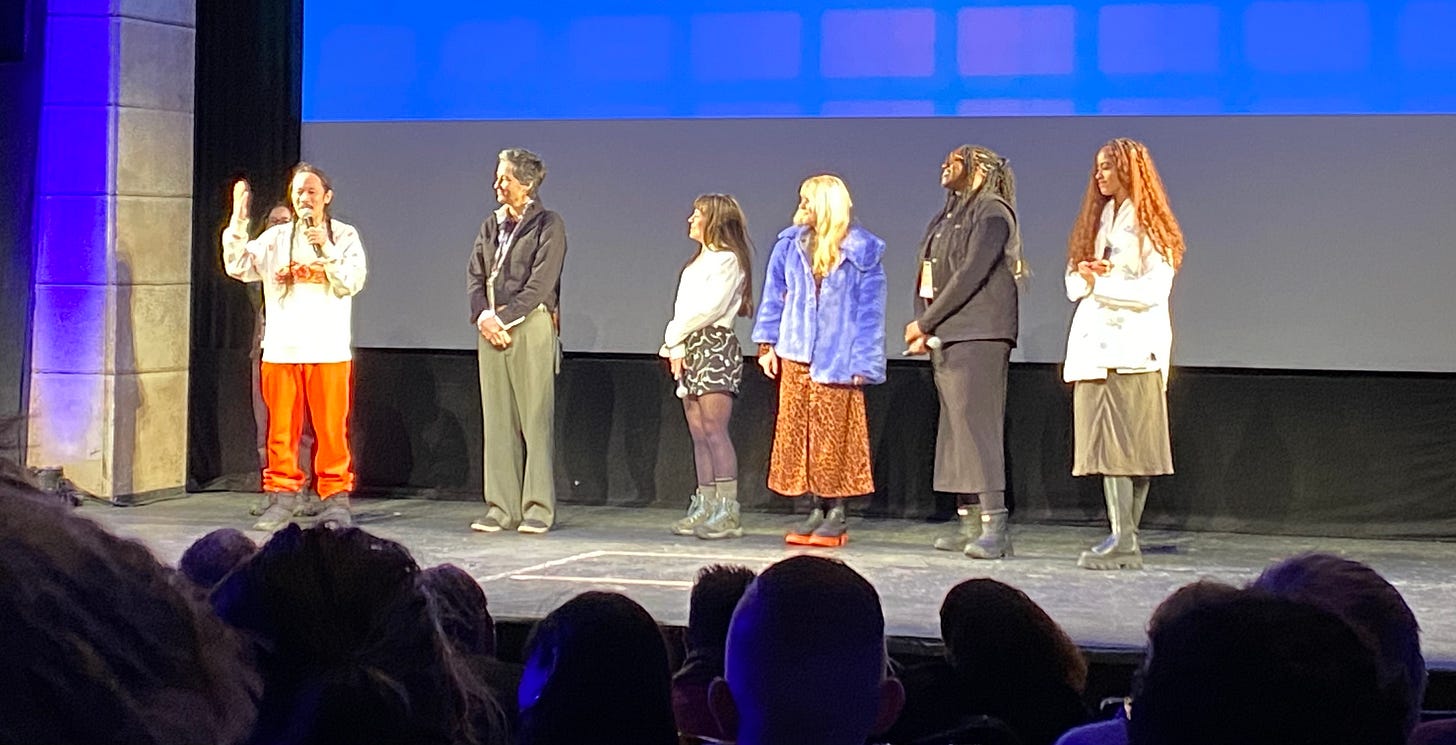

I managed to squeeze in a block of six short films during my weekend—on principle, one should always watch short films at festivals. Of the six, two were middling (Pathological and Miisufy), one was a dud (Alok), while the other three—Essex Girls, The Heart, and Pisko the Crab Child Is in Love—were stupendous. I can’t figure out why these six films in particular were placed into the same block—there is very little in common between Essex Girls, a coming-of-age story about an English teenager of Nigerian descent discovering comfort in her racial identity, and Pisko the Crab Child Is in Love, a delightfully imaginative and genuinely unexplainable tale of a girl with a crab for a father who then falls in love with her music teacher—but I also can’t complain at seeing six directors stand side-by-side onstage, explaining six viscerally different films to a captive audience. There was very little connective tissue between them, making it all the more rewarding.

The best of these shorts by far was The Heart, about as simple and effective as an eighteen-minute film ought to be. In it, we watch the quotidian and almost entirely wordless relationship between a mother (LaTonya Borsay) and her son (Tunde Adebimpe) before the mother dies of a heart attack. Her son is left grieving and regretful, and with an odd gift bequeathed to him in her will. Some of the scenes in the film are entirely without dialogue, and do a wonderful job conveying the familial proximity. The Heart was also directed by Malia Obama—yes, that Malia Obama—though I didn’t know this until well after leaving the theater. She went under the name “Malia Ann” in the credits, presumably to mitigate nepo baby criticism. Based on the quality of this project, I’d argue she doesn’t need to hide her name: the work speaks for itself.

I had two features left on the evening docket after the shorts, the first of which was Sue Bird: In the Clutch: a documentary about the Seattle Storm’s own GOAT point guard. A solid sports doc with an effortlessly charismatic subject at its center, In the Clutch portrays its subject as both humble and prideful. Why shouldn’t she be? Bird is the only WNBA player to win titles in three different decades, and has taken home a historic five gold medals at the Olympics. She consistently comes across funny and likeable, and effortlessly elucidates the sidelining of women’s sports over the past two decades. Anyone interested in basketball, power couples (Bird’s fiancée is two-time FIFA Women’s World Cup-winner Megan Rapinoe), the city of Seattle, or sports culture at large should look to see if and when this documentary arrives in a theater near them.

But a sports documentary—entertaining though it may be—is no way to conclude Sundance. I was hoping for something weird and off-putting: With the exception of The Heart, I had yet to be genuinely surprised by anything at the festival thus far; I wanted to be shocked into cinematic stupor. It was immensely rewarding, then to watch a sold-out screening of A Different Man, an A24-produced body-horror inflected dark comedy by writer-director Aaron Schimberg. The film tells the story of Edward (played by Sebastian Stan under heavy prosthetics), an unbearably shy actor with severe facial disfigurement. His disfigurement, meant to appear as facial neurofibromatosis, leads him to struggle mightily to connect with the outside world—all of which changes when Edward agrees to participate in an experimental medical procedure. The doctors tell him that the procedure will shed his disfigurement, but what they don’t tell him is just how much flesh-peeling it will take to get him there. There is one unflinchingly gnarly sequence in which Edward tears back layers of flesh and blood, stripping chunks of bumpy skin from his face that finally reveals Sebastian Stan’s hunky mug. This transformation prompts Edward to question who he is: Who has he become without his disfigurement?

A Different Man is possessed of a mean-spirited sensibility: it argues that Edward’s struggle to connect with the outside world isn’t because of his damaged appearance, but his personal inadequacies. That message risks tipping into cruelty, but Schimberg, a deft screenwriter, manages to consistently sidestep hatefulness, providing his characters with consistency and depth in equal measure. The resulting film is a strange and hilarious examination of the interplay between our interior and exterior selves, and how our self-perception defines who we are.

I was pleased that I could cap off my weekend with a movie as divisive as this one. Audiences left the theater alternating between states of shock, excitement, and utter distaste. I myself felt an unexplainable confluence of these same feelings as I walked home that night—the clearest sign of having watched something excellent. There’s no release date yet for A Different Man, but with a studio as big as A24 behind it, it is sure to come out sometime this year. When it does, be sure to check it out: Aaron Schimberg has created something unexplainably stirring, the kind of film that cannot be understood without experiencing it. I imagine that this is what Roger Ebert must have felt like after watching Charlie Kaufman’s Being John Malkovich for the first time in 1999. Schimberg, like Kaufman, has the kind of self-possessed depression that would come across despondent were it not for his instinctive wit and directorial prowess. Keep an eye out—he’s a filmmaker to watch.

James, Your talent shows when you offer your interpretation based on your knowledge and experience of the film industry. Keep up the good work!

This is awesome! - definitely makes me want to attend a big film festival!