The 2023 Airplane Mode Movie Awards

A recap of moviegoing in 2023, plus my top 20 movies of the year.

In 2023, I wrote a total of forty-one reviews, recaps, and industry thinkpieces. About 25% of those were recaps of the fourth season of Succession—a frankly unreasonable number of entries for a blog nominally dedicated to the movies. Still, Jesse Armstrong’s satire of would-be billionaire inheritors ended up being strangely relevant for a year in which studio chiefs raked in eight-figure compensation packages while dual labor strikes shut down Hollywood for a combined 191 days. While LA-based writers and actors were picketing in sweltering summer heat in a struggle for reasonable pay, media CEOs partook in the Sun Valley Conference in Idaho (otherwise known as the “summer camp for billionaires”), where they criticized the demands of writers as “just not realistic.” This is the kind of blatant, unsubtle contrast in which Succession made its name. When an anonymous executive said to Deadline that “the endgame is to allow things to drag on until union members start losing their apartments and losing their houses,” I wondered if HBO wouldn’t sue the AMPTP for plagiarism.

It was more than a little terrifying to see such ice-cold commentary rendered so plainly on the daily news, especially since this kind of cartoon villainy was typically the territory of, well, TV shows like Succession. There, the contrasts between billionaires and the working class were brutal, but cynically entertaining: absurd enough to be realistic, and realistic enough to be absurd. But then the labor strikes caused a $6.5 billion hit to the economy of Southern California and the loss of around 45,000 jobs, and we remembered why Succession was made in the first place. This was a show about income inequality so hateful, a billionaire man-child would cold-heartedly end the careers of an entire office building simply because his dad told him to. When studio CEOs decided it was better to push back their biggest releases (Dune: Part Two being the most notable absence) than pay their actors a fair wage, the message was the same: Money wins.

Except, of course, that money doesn’t always win: Both SAG-AFTRA and the WGA came out on top. The strikes concluded with the writers and actors securing impressive deals which secured their demands for streaming bonuses, staffing minimums, and regulations on AI; SAG-AFTRA in particular negotiated a deal worth over $1 billion for its members. This is no small feat for a labor movement continually deemed untenable by the powers at large, and moreover a signal that public support for artistic labor might be higher than expected. Around 67% of Americans expressed their support for the WGA and SAG-AFTRA during the strikes, and just under 50% expressed a less-than-favorable view of the major studios. In a world where corporations have relentlessly flooded our entertainment ecosystems with vapid content, the creatives seem to be on the rise.

But none of this strike talk goes any way in describing the year in movies. In 2023, superhero fatigue reached its apex growing audience disinterest coincided with lackluster movies like The Flash and The Marvels. 2023 also saw the critical and commercial rise of videogame adaptations as HBO’s The Last of Us took in record viewership numbers while The Super Mario Bros. Movie took second place at the year’s box office. And of course, 2023 was the year of Barbenheimer: a cinematic event so spectacularly, delightfully, and profitably weird, I’m still having a hard time believing it wasn’t a fever dream.

In light of these events, I’d like to try something a little different with this year-end recap. Rather than focus on a more straightforward top-10 list, as I did last year, I’d like to center this post on what I’m calling the 2023 Airplane Mode Movie Awards. In the list below, you’ll find a collection of awards based not on quality, but instead on movies that deserve mentioning based on the trends of the year. (If you want to see my top 20 films of the year, you can find it at the bottom of this post.)

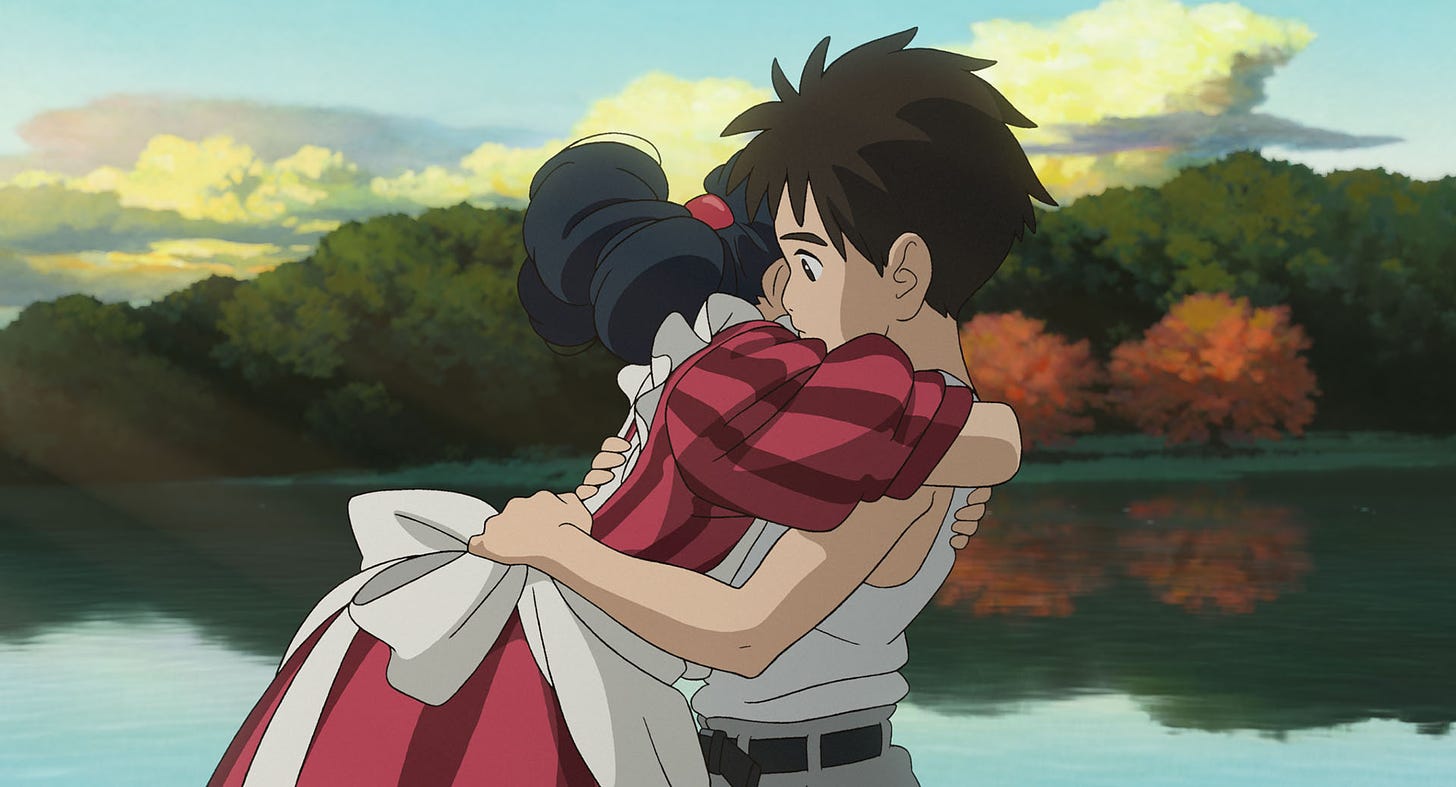

The Best Film of the Year: The Boy and the Heron

When it was announced that Hayao Miyazaki—the master Japanese anime director behind such masterpieces as Spirited Away, My Neighbor Totoro, and Princess Mononoke—would be returning to the director’s chair to make his 12th film, The Boy and the Heron, there was a hint of trepidation. He has retired no less than four times over the course of his five-decade career, the most recent of with the release of 2013’s The Wind Rises: a sendoff so fittingly self-referential, it was hard to imagine him creating anything else.

But now we have The Boy and the Heron: an abstract phantasmagoria of mourning, escapism, boyhood, and family legacy so magnificent, I feel ashamed to have ever doubted him. Set amid the destruction of World War II Japan, the film follows Mahito (Soma Santoki), a young boy who, after losing his mother in a Tokyo firebombing, moves to the countryside with his father and new stepmother, who happens to be his mother’s sister. In this new home, Mahito grieves his mother’s death in ways both literal and fantastical, as he plunges into a half-imagined otherworld created by his mysterious great-granduncle.

The Boy and the Heron bubbles with poignancy and imagination. It is even more summative than The Wind Rises, synthesizing all the most palpable images from Miyazaki’s career into a singularly transcendental experience. This is an overwhelming film, filled with detours into strange otherworlds that can at times feel unrelated to the film’s narrative. Many critics have resultingly failed to notice that The Boy and the Heron is an out-and-out masterpiece on a par with any of Miyazaki’s best works.

At 82 years of age, Miyazaki is delivering the kind of artwork that very few ever get the chance to complete. Like Martin Scorsese, whose Killers of the Flower Moon finds the great American director working in emotional registers he could never have discovered before his eighties, Miyazaki has tapped into the kind of profundity that comes once only every few years. The Boy and the Heron is Miyazaki’s greatest film, and belongs in the annals of the greatest films ever made.

The Worst Film of the Year: Saltburn

Saltburn, Emerald Fennell’s sexual satire of the English class system, is a tremendously terrible experience. This is a movie which promises a Talented Mr. Ripley-esque world of class-based romance, with some sumptuous visuals and two compelling leads (Barry Keoghan and Jacob Elordi) to boot. But Saltburn collapses into a pit of poor screenwriting decisions almost as soon as it starts, as Oliver, the film’s protagonist, inexplicably transforms from mysterious middle-class nerd to sexual schemer. The film’s central pleasures lie in gross-out scenes, such as those involving cum-stained bathwater and grave humping. And despite Fennell’s mischievous intentions, these scenes aren’t at all provocative. They’re just gross.

If nothing else, Saltburn proves that male hotness isn’t enough to keep a film afloat. This is somewhat remarkable when considering that Fennell did an expert job casting Jacob Elordi as her film’s object of desire. Elordi deserves all the credit in the world for turning his weirdo authenticity into movie stardom, and Fennell, to her credit, does an exceptional job shooting his six-foot-five hotness in a film that relishes in male genitalia. (As a side award, I will here be giving the Hunk of the Year Award to Mr. Elordi, for his dual performances in Saltburn and Priscilla. Honorable mention goes to Ryan Gosling, who single-handedly turned Ken into a sex object for men and women alike through his Oscar-worthy performance in Barbie.)

Saltburn is a poorly-written, poorly-executed, horribly-intentioned car crash of a film, but Saltburn has also found considerable success. The film leaped to #2 on last week’s Prime Video streaming charts; it has simultaneously inspired a rabid fanbase on Twitter and TikTok, who swarm around the film’s toxic sexuality. The film, in other words, has found viewership with a particular audience of particular tastes: a cult film. My good friend Siddharth Khare (who you can find writing about film at his great Substack, Noble Fool) observed this early on. “It is not a good film at all,” he wrote me. “But there is something iconic about it.” Saltburn is a movie that deals in disgust (and to Fennell’s credit, she is a connoisseur of filth), and while I can’t see that as anything other than unrepentantly terrible, but for those that enjoy a bit of beautifully-shot hot-boy smut, Saltburn may be your film of the year. Better this than The Marvels, I suppose.

Movie Event of the Year: Barbie

This award is a bit disingenuous, as the true movie event of the year was Barbenheimer: a once-in-a-lifetime double-feature that made a combined $2.39 billion at the global box office. But Barbie had a more visible cultural impact than its same-day competitor Oppenheimer. Beyond being the more profitable movie of the two ($1.44 billion at the global box office), audiences also showed up to the theater in style, sporting pink from head to toe in support of a film about a Barbie doll (Margot Robbie) undergoing gynecological existential.

This is not entirely surprising in and of itself: Warner Bros. led an exceptional marketing campaign. Through Airbnb rentals, a themed boat cruise, and an endless supply of pink, Barbie was eventized to ubiquity. But the reason that Barbie was the sensation that it was lies with the movie itself: a delightfully weird musical fantasia. The script, by Greta Gerwig and Noah Baumbach, is peppered with references to fascism, NSYNC, and Zack Snyder’s Justice League—an odd confection for a film set in a Day-Glo Barbieland heaven. The combination works, largely because Gerwig—a great director, and one of few millennial filmmakers to have achieved household name status—is able to synthesize cinematic wonder with pop-culture fun.

With a moviegoing economy that is increasingly depend on brand recognition and established IP, it’s easy to be cynical about Barbie’s success. One could easily describe the film as two-hour product placement, after all, and it’s hard to avoid thinking about the 14 other toy-based Mattel movies in the works now that Barbie was such a hit. The best comparison might be with 2008’s The Dark Knight: another billion-dollar pop sensation that presaged a coming wave of genre films. And where Chistopher Nolan’s Batman epic ushered in the age of superhero cinema, Barbie may do the same for original stories based on multinational consumer products.

Best Buy-Opic: Tetris

Speaking of consumer products, 2023 was the year of what film critic Wendy Ide has called the buy-opic: films like BlackBerry (about the phone), Air (about the Jordan shoe), or Flamin’ Hot (about the Cheeto). These are movies which chart the rise (and sometimes fall) of corporations and their consumer goods—a weird trend if there ever was one, and an uncomfortable sign that capitalist cynicism permeated every facet of our culture.

Then again, I did just praise Barbie for innovating upon a Barbie doll, so allow me instead to embrace the spirit of cynical optimism and say that Tetris, the Apple TV+ movie about one man’s journey to license and patent a bestselling video game, is an unreasonably good time. It would be wrong to say that Tetris is a great film, because it’s not. What Tetris does, however, is use the buy-opic formula to tell a swashbuckling tale of corporate rivalry. The film follows Henk Rogers (Taron Egerton), a game designer and licenser who embarks on a mythic quest to secure video game rights from villainous Soviet Russians, who are all but holding the game’s creator, Alexey Pajitnov (Nikita Yefremov), captive in his own home. So Henk, cowboy American hero, must maneuver his way into Soviet circles to rescue Alexey, his damsel in distress.

It’s notable that this film, like Barbie, succeeds only on the basis of self-awareness. Tetris screams of camp absurdity all throughout its runtime, keeping it from the capitalist self-righteousness of other buy-opics like Air and Flamin’ Hot. If these IP-based creation dramas are to continue, they would do well to follow in Tetris’ footsteps.

Best Biopic (That Was Secretly About Its Director): Oppenheimer

In 2023, big-name auteurs found themselves flocking around the biopic genre. Prestige fare such as Ridley Scott’s Napoleon, Michael Mann’s Ferrari, and Bradley Cooper’s Maestro have clogged up the upcoming awards season before it has even begun. There isn’t much tying these films together, but if like me you have an overt cinephile inclination, you may well notice that these movies are actually autobiopics: films not about their purported subjects, but instead about the filmmakers who made them. It’s something of a reach, but it can be fun to read Napoleon not as the story of a Corsican emperor, but as Ridley Scott self-assessing his own failures as a director; to read Ferrari as Michael Mann using Enzo Ferrari as a means of revisiting his own rags-to-riches story; or to read Maestro as Bradley Cooper self-analyzing his own artistic narcissism.

Of all this year’s prestige biopics, the one infused with the clearest self-portraiture is Oppenheimer, whose parallels are as obvious as they are silly. Nolan, like J. Robert Oppenheimer, is a man obsessed with scientific acuity as an end in and of itself. He is intent on parsing emotion through logic-driven formalism, as can be seen in films like Memento and Inception, and much the same way that Oppenheimer himself distilled a tragically human world into subatomic particles. There is also the suggestion of the Manhattan project as a representation of the filmmaking process, and particularly of the genius director struggling to hold it all together.

There is more than a hint of autobiography to Oppenheimer, but unlike Maestro, Ferrari, or Napoleon, that’s never really a problem, because Nolan never loses sight of Oppenheimer as a subject. He never falls prey to his personal predilections; he instead uses the Father of the Atomic Bomb as a vehicle for philosophical reflection. Oppenheimer is a frontrunner in this year’s awards season, and despite a number of flaws—not least of which is Nolan’s inability to write an actual human woman—it mostly deserves it. It is a not-quite classic American epic, but it is great, and a key film in Christopher Nolan’s increasingly autobiographical oeuvre.

Best Movie that Cost Over $200 Million: Killers of the Flower Moon

Want to hear the craziest moviegoing statistic of 2023? Out of fourteen studio movies that cost over $200 million to make, only one turned a profit. That’s a generally terrible sign for the tentpole movie economy, but there’s some consolation to be had in how Killers of the Flower Moon—an uber-expensive passion project from the 81-year-old Martin Scorsese—wasn’t necessarily made with profitability in mind. This is movie funded by Apple, a tech company so rich, it can spend $1 billion a year on movies and call it a passing interest. And as a result of this black-check benefactor, Scorsese was given free reign to create a brutally tragic story of white America’s relationship to its land and its people.

How are we then to judge the success of this film? For its budget, Killers of the Flower Moon made a measly $156.3 million: a box office bomb by anyone’s metrics. But in 2023, when Netflix regularly funds multi-million dollar blockbusters without the slightest consideration of profitability, that $156.3 million doesn’t sound quite as bad. Killers was never really supposed to succeed at the global box office, anyway. Apple funded the movie to win at awards season, and for all intents and purposes, it looks like the film will do exactly that. This is another frontrunner at this year’s Oscars: Leonardo DiCaprio and Lily Gladstone are sure to get Best Actor and Actress nominations; the film will also surely be nominated for Best Director, Adapted Screenplay, and Cinematography, and plenty of other technical categories.

Unlike in other parts of the world, the American studio system is based entirely on profitability. As a result, we are quick to judge cinema in economic terms. But it is also worth considering a film like Killers of the Flower Moon as a great piece of art, and nothing more. Movies are a more unstable medium than ever: Big Tech companies increasingly fund prestige productions that end up siloed away on formless streaming services, leading us to puzzle over whether a movie can even be considered a hit anymore. What we’re left with is the films themselves, and Killers of the Flower Moon, a poignant, devastating, and unusually expensive act of artistic self-reflection, should be understood as exactly that.

Best Action Movie: John Wick: Chapter 4

It would be hard to call John Wick: Chapter 4 underrated—any movie that grosses over $440 million at the global box office on a $100 million budget would be considered a hit. And yet this most recent entry into the John Wick canon, a globetrotting gun-fu epic with shades of Buster Keaton-esque comedy, has not been treated with the reverence it deserves. The first three films in the series were Hong Kong-inspired action epics, with Keanu Reeves starring as the titular action hero. Reeves’ stardom is magnificently suited to director Chad Stahelski, whose single-take action setpieces capture the delicate, violent precision of human movement.

Chapter 4 expands the balletic sensibilities of its predecessors to new heights. The film’s narrative is one of high-minded camp (John Wick seeks revenge against a grand network of secret assassins, etc.), and serves as background to action filmmaking of virtuosic skill and operatic scale. The mixture of gunplay and physical combat is immaculately choreographed, and Reeves’ body, a temple of slapstick comedy, always finds itself at the epicenter of stair-falls and drive-bys. The film is also a confection of magnetic performances: Donnie Yen, Bill Skarsgård, Laurence Fishburne, Shamier Anderson, and Rina Sawayama round out an impeccable cast.

John Wick: Chapter 4 is my fourth favorite film of the year, and unlike my other films of the year, the achievement of this film has nothing to do with its ideas. This is a movie that succeeds on craft alone: a film whose unimpeachable imagination takes it to magnificent heights. Few filmmakers could claim equal influence from both John Woo and Buster Keaton and mean it with any significance. But Stahelski and Reeves—action-comedy filmmakers working at a balletic apex—win that title with verve.

Best Christmas Movie: The Holdovers

Christmas ended a week ago, yet far too few people celebrated in the sad-sack spirit The Holdovers, the latest film from director Alexander Payne. It is Christmastime at Barton Academy, a posh New England boarding school in 1970, and there are but three “holdovers” left at the school—folks who, for whatever reason, can’t go home for the holidays. The trio of Paul Hunham (Paul Giamatti), a grumpy classics professor, Angus Tully (Dominic Sessa), a wisecracking student with an attitude problem, and Mary Lamb (Da’Vine Joy Randolph), the school’s head cook who recently lost her son in the Vietnam War, are delightfully acerbic and intimately performed.

Much like It’s A Wonderful Life, a Christmas film whose power stems from a brutal reckoning with depression and self-hatred, The Holdovers understands that the holiday season is often a terribly lonely one. Paul, Angus, and Mary are displaced figures in a season that expects them to joyful, and the bittersweet comfort that they find in each other over the course of the film is impressively authentic. The Holdovers earns its feeling of sentimentality more than any other film from this year: it is a Christmas classic in the making.

Top 20 Films of the Year

The Boy and the Heron

May December

Return to Seoul

John Wick: Chapter 4

The Holdovers

A Thousand and One

Asteroid City

Barbie

Oppenheimer

The First Slam Dunk

Fallen Leaves

Killers of the Flower Moon

Priscilla

Past Lives

Knock at the Cabin

The Creator

Anatomy of a Fall

El Conde

BlackBerry

Reality

Appreciate your insight and clear writing. Will be very useful in our movie selections.👍

One of the finest year-end pieces I've read. Kudos for writing about the topicality of Succession in such a cogent form 🙌🙌🙌